The majority of local authorities have failed to build a single council home in the past five years, according to shocking analysis that lays bare the scale of the social housing paralysis.

There are now more than 1.2 million families on the waiting list for properties, but figures show that in 2021/22 only a third of England’s local authorities completed any new build homes. Further investigation by The Independent also revealed that, during the annual year of 2022, more than half of councils did not build a single house.

Our findings come weeks after it emerged that Michael Gove’s department handed back £1.9bn to the Treasury, originally meant to tackle England’s housing crisis, after reportedly struggling to find projects to spend it on. Officials said the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) was unable to spend the money due to rising interest rates and uncertainty in the housing market. The money included £255m meant to fund new affordable housing and £245m meant to improve building safety.

The waiting list for council homes has risen by over 88,000 households in five years, with many of those waiting forced into unsuitable private accommodation in the meantime.

There are fears rising rents, which hit a new record high this week, will mean that many are totally priced out of the housing market, with research showing that people receiving housing benefit can now only afford four per cent of private rental homes. The property website Rightmove has said the average rent being asked outside of London for a private rental has risen to £1,231 per month, while the asking rent for new tenants in London is at a record £2,567 – up a third in three years.

One housing action campaigner told The Independent that houses large enough for a family of five only came up once a year, and many families were forced into one-bedroom homes in the meantime. Councils say that they struggle to build more homes for social rent because of a lack of funding from central government and restrictive measures in the way they can finance new builds.

Shadow housing secretary Lisa Nandy said that "housebuilding is falling off a cliff because the Conservatives crashed the economy and Rishi Sunak rolled over to his own MPs on housing targets, there is no solution to the housing crisis that does not involve a substantial programme of social and affordable house building.”

‘There’s mould on the walls, it’s black and totally wet’

Yuli Rodriguez has been on the waiting list for a council home in London for over three years. She told The Independent that her two oldest children Emily, 12, and Adrian, 10, have to sleep in the living room of her two-bed private rental flat because of the water that leaks from the roof in the second bedroom. Her youngest child, Thiago, aged two, has developed breathing problems that Ms Rodriguez believes are caused by the mould on the walls.

She recalled “I was sleeping with my baby recently and the water was coming from the light in the ceiling. All my bed was totally wet and I called my landlord and he didn’t pick up. I sent so many emails but he doesn’t want to repair anything. There is mould on the walls. It is black and the wall is totally wet.”

Baby Thiago was diagnosed with a respiratory tract infection and given antibiotics to manage his wheezing in the summer of last year. Pictures show the ceiling of the small bedroom covered in water droplets of condensation.

Juana, 51, who works as a cleaner, has been in temporary accommodation in Lambeth for three-and-a-half years while she waits for a permanent council home to become available. She was moved into her current flat after fire service officers and council workers arrived at her previous home and told residents they needed to move out immediately because it was unsafe.

She told The Independent: “It’s stressful waiting and you don’t know when you might be moved out again or where you might be going.”

She explained that when she first arrived at the flat, with her husband and teenage daughter "it was not furnished, we were sleeping on the floor for about six to eight months because we didn’t know how long we were staying there. We didn’t have any bed or anything to bring with me. There was just a cooker and a washing machine and a fridge, that was all the house had. I had to buy all the things from scratch. I was just sleeping on the carpet with a blanket.”

‘Renaissance’ needed

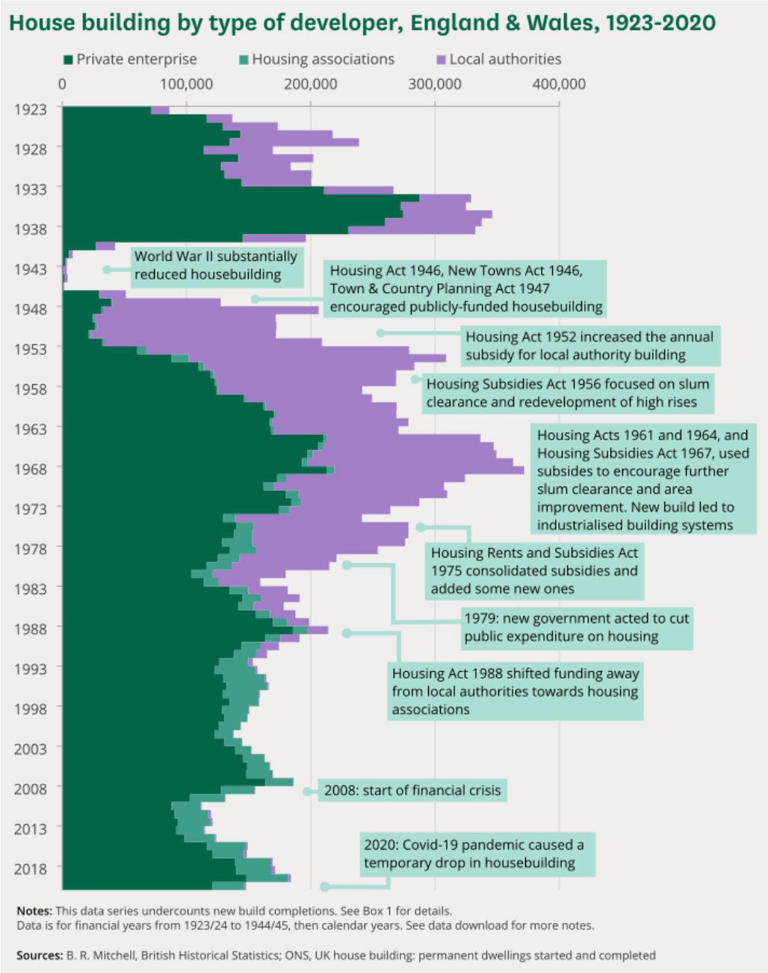

The drop in local authorities building houses has been stark in recent decades. More than 100,000 homes were built a year in England during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, which has dwindled to a few thousand annually in recent years, according to data from the Department for Levelling Up.

In each year of the last five financial years, two-thirds of councils failed to build a single home, analysis of the government data shows. In 2021-22, 207 out of the 307 councils that provided data to the government had not built a home in that year. A snap survey of district and borough councils in England carried out by The Independent also found that just over half of local authorities did not build a single home in the annual year 2022. Of the 148 that responded, 80 said they had not completed a home last year. This was compared with 73 who had completed no house builds in 2021.

Councils were historically big builders of housing (House of Commons research library)

© Provided by The Independent

Birmingham council had completed the most new homes, with 185 properties in 2022, 97 of which were for social rent. Islington council had delivered 178 properties in 2022, 136 of which were for social rent. And Rotherham metropolitan borough council had delivered 124 homes, with 90 built at affordable rates, 20 for shared ownership and 14 for market sale.

Charlie Trew, head of policy at housing charity Shelter, said "cuts during the period of austerity meant a council’s ability to build housing was stripped back. Changes in grant funding from central government have also added to the problem and left councils increasingly reliant on cross-subsidy (where councils build a mixture of social rent properties and properties to privately rent), we would like to see a renaissance in council house building, particularly socially rented homes. We would like to see many more councils getting back into the business of it.

Talking about the benefits of council-built homes, Mr Trew said “you’re not getting very many numbers [of social rent homes] through private development because the developer is trying to maximise profit. They are trying to cut the delivery of those homes as much as possible, whereas a council who is responsible for the social housing wait lists and for homelessness has a direct incentive to build homes that are genuinely affordable to local people.”

’The government needs targets’

Elizabeth Wyatt, at the Housing Action Southwark and Lambeth, has seen how the shortage of council homes impacts those in her borough. “If you need a family-sized council home, then you have to wait years and years. In Southwark, you see one five-bed come up once a year for example. The more bedrooms you need, the longer your wait is. Lots of families are overcrowded in a one-bedroom home, which they would happily give up, but the family-sized homes are just not there.”

Explaining the difference in rents, she said “housing associations will offer social rent, which can be really similar to council rent, but they also offer affordable rent, which is 80 per cent of market rent. That’s hundreds of pounds of rent difference per week and compared to council rent it is really unaffordable for a lot of families.”

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has faced criticism for dropping the mandatory target of building 300,000 new homes a year by the mid-2020s. The national target, based on the estimate number of homes needed to keep pace with demand, was introduced in 2017 by then chancellor Philip Hammond. But last year Liz Truss branded the target “Stalinist” and said it should be scrapped. Mr Sunak’s government has said the target still exists, but that it is now “advisory” rather than “mandatory”.

Labour has promised to reintroduce the targets and to restore 70% home ownership. They have also pledged to build hundreds of thousands of new council homes, saying that local authorities will not be allowed to opt out of building homes.

Councillor Ahsan Khan, Newham’s member for housing, said that the "scrapping of housing targets was a mistake. The government needs to have targets and it needs to incentivise all sectors, in particular councils, to bring forward council homes for people on housing registers right across the country.”

Councillor Diarmaid Ward, from Islington council, said “it costs about £300,000 to build a council home in London and the government grant only covers about a third of that. So you’ve got to find the other two-thirds somewhere. Added to that you’ve got Right to Buy, which depletes the council housing stock. If you mix in the twin evils of inflation and interest rates, it makes for a very difficult environment.”

The Local Government Association, which represents councils, has called for a “genuine renaissance in council house building”. They have welcomed recent government measures to lift the housing borrowing cap and to allow councils to keep all Right to Buy receipts for two years.

However, they have asked for councils to retain 100% of these receipts on a permanent basis and for a new national task force to be set up that would provide additional help for councils who want to get building.

A spokesperson for the DLUHC said the government is supporting councils “by investing £11.5 billion to build thousands more affordable quality homes”. They added: “Since 2010, we have delivered over 632,000 affordable homes in England, including over 162,000 for social rent, and are committed to increasing this number”.

Consultation launched to hear from social housing landlords about new proposals

The Regulator of Social Housing (RSH) has launched a consultation on new consumer standards for all social landlords.

Following the Social Housing Bill becoming law the consultation aims to hear from social housing landlords and tenants about the proposed standards in the Bill. The Bill is being hailed as landmark legislation in the social housing sector.

Biggest change to social housing regulation for a decade

Fiona MacGregor, chief executive of the Regulator of Social Housing, said “all social housing tenants deserve to live in safe and decent homes and receive good-quality services from their landlords. We’re proposing new requirements to make sure this happens. We encourage tenants, social housing landlords and others in the sector to have their say through our consultation. We’re gearing up for the biggest change to social housing regulation for a decade. This will include our landlord inspections from next April, as well as stronger powers to make landlords put things right when they breach our standards.”

Give more power to tenants

Social landlords (including councils and housing associations) already need to comply with standards set by RSH.

However, the proposed standards are set to give more power to tenants by strengthening the safety requirements that all social landlords need to meet. The standards will also require landlords to know more about the condition of their tenants’ homes and the individual needs of the people living in them.

The Act also includes Awaab’s law which will require social housing landlords to fix reported health hazards such as mould within strict time limits.

Shelter back on the warpath over Section 21 evictions

Campaigning charity Shelter has renewed its calls for the abolition of S21 eviction powers. It says new Ministry of Justice data shows the number of households removed from their homes by court bailiffs as a result of S21 is up 41% in one year in England.

Shelter claims that between April and June 2023, 2,228 households were evicted by bailiffs because of a Section 21, up from 1,578 households in the same quarter last year. Private landlords started 7,491 court claims to evict their tenants under Section 21 this quarter, up 35%. The charity states that 24,060 households were threatened with homelessness as a result of a Section 21 in the past year – up by 21% compared to the previous 12 months.

Polly Neate, chief executive of Shelter, said “with private rents reaching record highs and no-fault evictions continuing to rise, hundreds of families risk being thrown into homelessness every day. Landlords can too easily use and abuse the current system. Some will hike up the rent and if their tenants can’t pay, they will slap them with a no-fault eviction notice and find others who can. We speak to renters all the time who feel like they have zero control over their own lives because the threat of eviction is constantly hanging over them. The Renters Reform Bill will make renting more secure, and for those who live in fear of the bailiffs knocking at their door, these changes can’t come soon enough. The moment Parliament resumes, the government must get rid of no-fault evictions which have made the prospect of a stable home little more than a fantasy for England’s 11 million private renters.”

Homelessness crisis looms as councils struggle with demand

Councils across England are struggling with a surge in demand from households facing homelessness with nearly a quarter of a million households looking for a home, one organisation reveals. The findings from Crisis are part of its annual ‘state of the nation’ survey and it found that the equivalent of 1 in 100 households are grappling with homelessness.

The trend is pushing thousands into temporary living arrangements like B&Bs and hostels, as local authorities struggle to secure long-term housing solutions. The research was carried out by Heriot-Watt University which found that the factors driving homelessness levels up include rising living costs and rents.

‘Temporary accommodation should be a short-term emergency measure’

Matt Downie, the chief executive at Crisis, said “the homelessness system is at breaking point. Temporary accommodation should be a short-term emergency measure yet, as the report shows, it is increasingly becoming the default solution for many councils. This is leaving thousands of people living out their lives in a permanent state of limbo, enduring cramped, unsuitable conditions – with a fifth of households in temporary accommodation stuck there for over five years. It comes as no surprise that councils are reporting that they are running out of temporary accommodation.”

85% of councils in England are witnessing a surge in homelessness

The survey found that 85% of councils in England are witnessing a surge in homelessness cases, marking the highest proportion since the survey began.

The combination of a housing benefit freeze, a dwindling supply of social housing and a scarcity of affordable private accommodation is creating a challenge for local authorities. Research shows that 88% of councils are dealing with more requests for help from tenants being evicted from the private rented sector (PRS) and 93% of councils are predicting further increases in the coming year.

‘We need to provide security to low-income households’

Mr Downie said “for too long the emphasis has been on managing homelessness, not building the social homes we need to provide security to low-income households. The alarm bells are ringing loud and clear, the Westminster government must address the chronic lack of social housing and increase housing benefit, so it covers the true cost of rents. We cannot allow this situation to escalate further and consign more lives to the misery of homelessness.”

Growing competition for a dwindling supply of homes to rent

The report also reveals that rising rents in the PRS and growing competition for a dwindling supply of homes to rent is leading 97% of councils struggling to source suitable private rentals over the past year.

As access to social housing also dwindles, councils are increasingly turning to the PRS to house low-income households, but the challenges are becoming insurmountable and as councils exhaust their options for sustainable long-term housing solutions, they are resorting to temporary accommodations at an unprecedented rate.

Crisis says that the number of households living in such arrangements has reached a record high.

However, it appears that this approach is nearing a breaking point, with councils expressing concerns about their diminishing capacity to secure more temporary accommodation.